The untold story of just how close Bernie Brookes got to being the man to turn out the lights at SA’s largest clothing retailer, Edcon, is the stuff of nightmares. Not just for its 48,000 staff but for the entire country, which is largely unaware of just how close Edcon came to tipping over and triggering a chain reaction that would have rocked the banks, property companies and consumers.

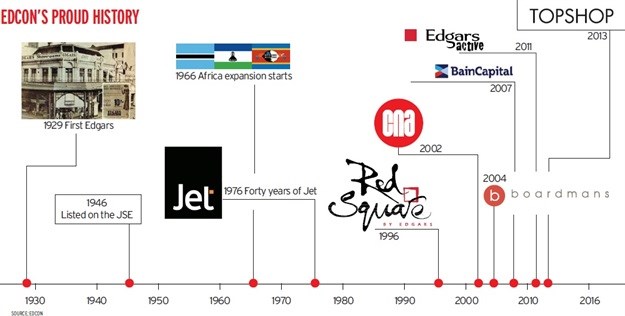

Since the brothers Morris and Eli Ross opened their first store on September 6 1929 in Joubert Street, Jo’burg under the name "M&E Ross, trading as Edgars", the company has become a pillar of SA’s business landscape. (Sydney Press, who began as a casual worker in 1935, was the chairman when it listed on the JSE in 1946, clocking up £536,000 in turnover from its 10 stores).

As it stands, one in five South Africans shop regularly at one of Edcon’s 1,542 stores – at its main clothing arm, Edgars, its discount store Jet, or the once-mighty newsstand business, CNA.

It was such a superstar of emerging market retail that, in 2007, it caught the attention of US politician Mitt Romney’s private equity firm Bain Capital, which forked out an unprecedented R25bn to win control.

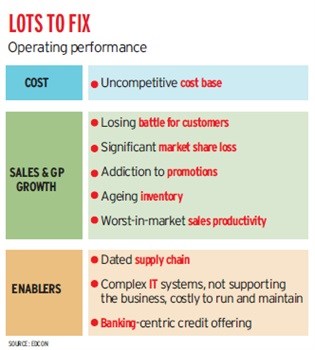

It was a disaster, in part because the global financial crisis struck a year later. To repay this huge debt, Edcon had to stump up R4bn a year to financiers, crippling its main business. And with no money to invest in new stores or customer service, its market share plunged from 32% in 2007 to 25%.

In March this year Edcon lurched to the brink of becoming SA’s largest corporate failure since Saambou Bank crashed in 2002.

Speaking to the Financial Mail, Brookes, a 57-year-old Australian who took on the CEO’s job, says the company had run out of cash and ideas — so it took the tough decision to default on payments to its creditors. "It was a burning platform, which meant the business was not going to survive and not going to be sustainable, and the board took the risk to not pay our banks and creditors in March and so commence negotiations."

Reluctantly, the companies that owned Edcon’s debt — large banks including Barclays Africa and FirstRand, as well as overseas institutions like Franklin Templeton — sat down to discuss options.

It wasn’t easy. Many believed Edcon should have been allowed to collapse and go into "business rescue", rather than be bailed out. Edcon debated selling off its assets but the offers were derisory.

"(They were) looking for gold bricks for a dollar," says Brookes. "Many wanted to buy Jet at an absurd price because we were obviously on our knees with a beggar’s bowl, not paying suppliers. So they were like vultures, taking advantage of that."

Between November and May, he spoke to every major SA retailer and some international ones, hoping for a white knight. All these overtures failed. At one stage, finance minister Pravin Gordhan supposedly met retail tycoon Christo Wiese to interest him in using one of his companies to save Edcon.

Landlords who rely on Edcon as anchor tenant in major shopping centres, where the store typically owns up to 10% of the space, began scenario planning, looking at who might replace Edgars when it went bust.

Brookes and his team have had 60-80 major meetings with creditors over the past six months, some dragging on until dawn.

It could have gone either way.

The outlook was so grim that a "business rescue practitioner" was appointed in August. This jolted creditors, who realised such a bid to "save" a company often fails.

Brookes says that for some weeks, business rescue seemed "the most likely option".

It would have been a mistake. Says another insider: "Nobody would have made money out of it. The consequences would have been severe."

And perhaps if it had been 2008, before Lehmann Brothers fell in the US, the banks might well have let Edcon fail. But after the financial crisis, the banks had developed a visceral fear of letting any company collapse. Everyone had become "too big to fail".

The banks and bond holders resumed talks. Cranky at the prospect of losing part of their investment, some nevertheless agreed, albeit reluctantly. Others took their time but, in the past few weeks, everyone signed the deal. It ended up as SA’s most ambitious debt-to-equity swap, which will result in the companies owed more than R20bn by Edcon dropping their claim in return for shares in the retailer.

This leaves Edcon with a far more manageable R6.7bn in debt. Bain Capital, having ploughed R6.4bn into Edcon, walks away entirely, tail between its legs.

"It’s been a monster task for all concerned," says Brookes. "When I announced the deal to our landlords I thought some of them were going to burst out into tears."

Edcon’s new shareholders include Franklin Templeton, Brigade Capital, SA’s big banks (specifically Barclays Africa and FirstRand), and the Harvard Pension Fund.

"It was a bit of a rollercoaster where you did envisage that business rescue was going to (happen). It wasn’t until late August that it became most likely that there would be a rescue package. The end game was never really obvious," says Brookes.

Some creditors ended up losing part of what they’re owed — something Brookes describes as a "haircut on the basis of re-growing the hair, if you like". But the bottom line for Edcon is that the debt repayments drop from R4bn/year to R500m/year.

It’s not a guarantee of salvation, given the pillaging and negligent lack of investment for a decade, but Edcon has a shot at survival. Brookes warns: "Don’t underestimate how bad the debt situation was."

So can Edcon be rebooted? The jury is very much out on whether this new deal is enough to do that and restore the powerhouse, going back to the days before Bain waltzed in. Some say Edcon has fallen so far behind rivals like Woolworths, Mr Price and Cotton On that it can’t make up lost ground.

To assess its chances of a recovery, it is necessary to take stock of the deep wounds inflicted on the wider Edcon body.

The damage goes further than failure to invest in new stores: the huge debt sapped morale, soured supplier relationships, and talented staff found other jobs.

"Nobody wanted to come and work for us," says Brookes. "And if they did, we had about 30% staff turnover because people weren’t certain of the future: if we did go into business rescue they’d have no job."

Debt payment also meant a perpetual round of retrenchments. Already, 35% of the head office jobs have been slashed, though Brookes says no more cutbacks are planned.

Anything not nailed down was flogged in a scramble to pay Bain’s debt.

Stock from suppliers dried up because the credit risk was too high. For example, if CNA needed 10,000 calculators for its "back-to-school" promotion, suppliers would give it only 1,000. If the new iPhone was being released, CNA was at the back of the queue.

Edcon’s internal systems were also a mess. Until last year it was paying 192 advertising agencies to sell its brands, which resulted in a net R64m loss selling its international products. R600m of stock, some of it two years old, is still waiting to be moved. Brookes has now cut the number of ad agencies to three.

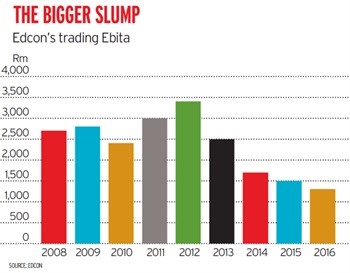

It’ll be tough to reverse course. Figures for the year to June, released two weeks ago, were predictably awful. Edcon sales fell 1.3% and overall profit was down 1.7%, signalling falling margins.

Richard Vaughan, Edcon’s third chief financial officer in four years, attributes this partly to a general weakness in retail, as consumers are badly stretched. In the first quarter, SA retail credit sales dropped 10.3% and cash sales fell 5.3%.

So for the first quarter (to September) of Edcon’s new financial year, the decline continued, with sales down 1.3%.

Brookes does not expect the second quarter to be much different. He estimates full-year profitability will be 30% down on last June. "It’s pretty hard to go fast when you’re taking out the engine and fixing every aspect of it."

Productivity is also low: Edcon is making R7,000-R8,000/m², far less than the R24,000-R30,000 of its competitors.

This means changes are also needed where it matters most — on the shop floor.

While much of the disaster was being played out within the dour walls of Edgardale, the group HQ in Crown Mines in the south of Jo’burg, it was in the stores that Edcon took the biggest beating. Brookes says customer service pretty much ground to a halt, so that Edgars became virtually a self-service store.

"There’s no other department store in the world where you self-service. They did this to reduce cost. There’s been no investment in training to serve customers," he says.

With so much energy going into keeping the business afloat, staff just weren’t trained, says Sasfin Securities analyst Alec Abraham. "Customer service in stores is shocking. They have to do a lot of work."

Customer comments were brutal. Former customer Johanna Davidson said on Facebook: "I haven’t shopped there in years because of their appalling service. I prefer to spend my hard-earned cash where I’m treated with respect". She found staff at H&M "brilliant", the goods " cheaper" and the fashion "more up to date".

One of the most contentious moves of Brookes’s predecessors was to bring in expensive foreign brands, like Dune, Tom Tailor and TM Lewin. But this jarred with the solid, home-grown value-brands shoppers wanted and were used to.

It was a dismal failure.

"Half the brands they brought in, nobody had even heard of," says independent retail analyst Syd Vianello. "If H&M comes to SA, people know who it is. It’s a global brand — a lot of Edgars customers travel abroad. What is Lucky Brand [one of the labels brought in by former CEO Jürgen Schreiber]?"

Launching these brands cost big money too; there’s a franchise fee or royalty, which reduces gross profit margin. And at the same time, Edgars was neglecting its high-margin "private-label" items.

Bain, says Vianello, was obsessed with gross profit on every item sold. "A price point was established and the cost was engineered to a level where they could make the gross profit. So quality had to be cut."

Better options by Mr Price and newbies like Cotton On had grabbed customers’ attention, as local retailers began to up their game in anticipation of the global fashion onslaught of Zara and H&M. Consumers had cheaper, trendier options.

"I don’t think the expat CEOs really understood the significance of Edgars in the SA context," says Abraham.

Brookes has spotted the error and made a U-turn on the international brands. While some — like TM Lewin and Topshop — will remain, others will go, including Lucky Brand, whose jeans sell for R2,400 a pop.

But this fashion volatility illustrated a deeper problem within the group.

Fashion has always been a problem for Edgars, says Chris Gilmour, an analyst at Absa Investment. "They did try fashion and they failed and had all those red hanger sales and would flog things. The likes of Truworths and TFG were always more fashion-orientated. Edgars has only ever been on the fringes of fashion."

Part of the problem, says Vianello, was the ever-changing management layer. "It takes at least three seasons to get [a clothing business] right and the fourth season to perfect it. In the process of changing teams you simply set the clock back to stage one again. This was a big part of the problem."

Edcon, it seemed, didn’t know who it was. To make things worse, it was facing problems in another stronghold — credit.

Ask people about their first memories of Edgars and chances are it’s the first store that sold to them on credit.

Edgars were pioneers. The story goes that during its inaugural spring sale in 1929, the manageress, Ms Kent, approached Eli Ross and asked him what to do about a customer who wanted to buy an item of clothing but didn’t have enough cash. "Take what she has got and let her pay the balance at one pound per month," Ross said, according to University of Stellenbosch research.

And so began an institution which led to more than 12m Edgars card holders. Everyone had a card or knew someone who did — it was the Edgars way.

"In the apartheid days, Edcon was a banker to the nation," says Sasfin’s Abraham. "It extended credit to the mass, unbanked population who couldn’t get credit through the formal banking system. [Edgars] was in all the outlying areas – it had a strong footprint and sold functional but aspirational clothing to the market."

After Bain bought it, Edcon came under pressure to sell its credit book to get much-needed cash flow. It sold its debtors’ book of 3.8m customers to Absa for R10bn in 2012 — and the wheels really started to come off.

Absa, having just been through the global financial crisis, was in no mood to be as generous with credit as Edgars was. It began closing the taps and even good Edgars customers struggled to get credit.

Credit sales dived from 60% of Edgars’ overall sales to 38% today, as the credit book fell by nearly a third.

The timing was bad: in 2007 the National Credit Act put the squeeze on lenders, shifting the onus of ensuring that debt was affordable from borrower to lender.

For Edcon, which had signed up 2m credit customers in the four years preceding the act, it was a disaster.

SA’s retail sector immediately shifted to discount fashion retailing based on cash. Mr Price soared. Edcon, a brand with credit extension in its DNA, needed a new approach. Under then-CEO Schreiber, it was so focused on making its debt payments that it missed that trick.

Now Edcon is planning to do its own lending to certain customers who have been shut out by Absa, to address this scenario.

While critics have slammed Bain, Brookes points out that it invested 75,000 hours in Edcon and put in R6.4bn of its own money — which it won’t see again.

"They could simply have put the business into business rescue but they worked with the creditors and managed to ensure the future of the 48,000 people and a 250-strong supplier base," says Brookes.

Sure, but Bain had probably worked out that it was best to cut its losses.

The plan is for Edcon to gradually recover, before being listed again on the JSE by 2019 or 2020. Brookes’s blueprint includes a renewed focus on customers, big changes n the shop floor, a less hierarchical structure and a R600m investment drive.

There’ll be fewer foreign brands, as Brookes is streamlining from 37 brands down to a dozen. It makes sense: about 70 of the group’s stores have international brands which bring in an average R7,000/m², compared with R17,000/m² for a standard Edgars store, and R24,000/m² for private-label brands. The international brands it plans to keep are TM Lewin, Topshop, River Island, Doc Martens, Dune, Accessorize, Inglot and about four or five smaller ones.

The new focus will be on "private-label" brands – in other words, homegrown brands like Kelso and Stone Harbour.

"They’re great products and beautifully designed," says Brookes. "We have half a dozen young SA designers developing the product. It’s not copied from elsewhere and we’re going back to the sketch books."

Each store manager will also have more autonomy, a change from the hierarchical model of the past where everything was dictated from the Edgardale mothership.

The approach to pricing is changing, too: who can forget those red hanger sales?

Pricing became a haze: Edgars would price products up, in order to price them down. It would market entry-level jeans at Edgars for R259 and then sell them for R189 on special. Other retailers were selling the same items at R189 or R199.

Edgars is now slashing its reliance on promotions, but dropping prices to be more competitive to start with.

It is also shutting stores — about 10% of its 1,542 stores will be closed over the next three years. "We’re seeing a high cannibalisation rate in our new stores. When we opened in Mall of Africa, it had a big impact on stores in Centurion and Midrand," says Brookes. This is a consequence, he believes, of SA becoming "over-malled", with retailers having far too many stores.

"We have quite a few Edgars branches within a 5km radius of each other. Or a Jet next to a Jet Mart. If you look at most other countries, whether it’s a Macy’s or Myer or Selfridges, they all build stores a long way away from one another. What we’ve done here is open far too many stores."

Edcon is to spend R600m refurbishing about 60 stores over the next few years.

It doesn’t deal with all its problems (among them the Melrose Arch store in Jo’burg) but it’s a start.

"I’m not sure what the deal was with Melrose Arch, but we have to stay because we have a 10-year lease. But it’s not performing," says Brookes.

There has been talk of Edcon selling off noncore brands. Two weeks ago, it announced it would sell Legit for R637m to Metier Private Equity. But Brookes says they’re not in a hurry to sell assets.

For the businesses that are broken – like CNA or Boardmans — Brookes’s plan is to fix them, before discussing selling them.

"Will we sell them all? No. Are we going to sell in a hurry? No. Are we going to fix them up first, like CNA? Yes, because if CNA is making only a few million rand profit you’re not going to get any money for it."

But the billion-dollar question is, will his changes rescue Edcon? Or has its lunch already been eaten by the slicker operators, like Woolworths?

Brookes, interestingly, doesn’t see these international brands as his biggest threat.

"Everybody said when I arrived that a lot of the international brands are doing quite well. Cotton On is doing very well. But there are just as many that aren’t performing. Don’t get me wrong — there’s a place for H&M in a limited number of stores. And (we took an) initial hit from H&M here, but we then learnt to re-engineer product."

In Sandton City, for example, Edgars lost many customers — mostly young girls — to the H&M store. "But we’ve managed to claw that back over the past six to 12 months, and the same with the V&A Waterfront," he says.

Brookes’s real goal is to fix Edgars and Jet, which still provide 85% of Edcon’s sales.

He has also set targets — which don’t look that ambitious, but probably are, considering its current trajectory.

Over the next four years, Edcon is aiming for 2% growth in sales and profitability.

Profits will go down, before they go up, as it invests in new stores. "But eventually, if we get back to the profit of this year, which was R2.8bn, it gives a marvellous opportunity to (list) on the (JSE)."

The real trick will be to convince the market that the "new Edcon" is worth investing in. This is a function, he argues, of "time and communication" — speaking to staff, suppliers and landlords at every turn.

If Brookes succeeds, the likes of Woolworths and Truworths, Pep and Mr Price who "had the luxury of being able to steal market share from us" will be in for a shock.

"It’s because we’ve been impotent on price and service and range. So if we become a force — and our plan is to do so — we will probably have negative sales this year and probably head back to positive sales from then," he says. Rivals "won’t have it as easy as they have done".

Edcon’s suppliers appear relieved by this new deal. Mark Sardi, CEO of the House of Busby, which provides brands like Topshop and Mango in the Edgars stores, believes Edcon now has the strategy right — focused on own labels and higher-margin product.

Alex Borkett, a senior manager at Jo Borkett, one of the first upmarket fashion brands to be sold through Edgars, has nothing but praise for Brookes. "We’re very positive. The changes coming from the top are filtering down through the business, evident in the new product offerings, supply chain and customer service," he says.

Others remain sceptical. Vianello doesn’t believe Edcon will list in four years. "I don’t see the creditors as being long-term shareholders — they know that they have lost a fortune already. If someone came along and offered them [individually] a fair price for their shares, they’ll take a cheque. " Banks, he says, aren’t retailers.

He implies that Edcon needs a far bigger overhaul if it is to hold its own in the new era of SA retail. Its old model of being a "family outfitter", a middle-income retailer with something for the kids, granny and the parents, doesn’t work any more.

"They need to go back to where the margin is: private label," he says. "They need to get the trends and fashion right. Woolies and Truworths and TFG, sell one brand of product — it’s all theirs. They design it, source it and import it, distribute it, sell it."

Abraham agrees: "I don’t think Edgars is going to start taking back market share soon — the other retailers still have a little bit of time. Edgars will actually lose market share purely from closing stores."

Still, and for the moment, Brookes looks like a weight has been lifted from his shoulders. "Our employees now see us as a nice place to work, and they’re going to get paid and have a future. Credit insurers are no longer banging on the door; landlords now see us as a preferred anchor tenant because they know we’re going to be here for the (duration) of the lease," he says.

It may not be much, but it’s a damn sight more secure than it was four months ago.

With additional reporting by Zeenat Moorad; image credit: Financial Mail

For more than two decades, I-Net Bridge has been one of South Africa’s preferred electronic providers of innovative solutions, data of the highest calibre, reliable platforms and excellent supporting systems. Our products include workstations, web applications and data feeds packaged with in-depth news and powerful analytical tools empowering clients to make meaningful decisions.

We pride ourselves on our wide variety of in-house skills, encompassing multiple platforms and applications. These skills enable us to not only function as a first class facility, but also design, implement and support all our client needs at a level that confirms I-Net Bridge a leader in its field.

Go to: http://www.inet.co.za