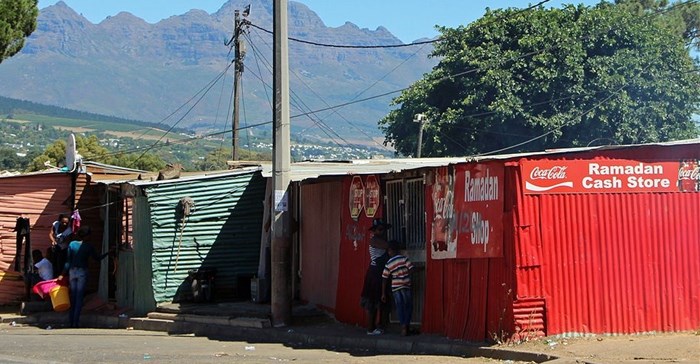

Spaza shops, which began in the mid-1970s, derive the name from vernacular township slangs word meaning an ‘imitation’ of a real shop. From the Zulu verb ‘isiphazamisa', it also means hindrance or annoyance possibly referring to the way in which these shops were either viewed by privileged segments of society and larger retail outlets or by those that lived close to these shops and became annoyed by foot traffic and noise. Moreover, today, the latter has been reversed as several hindrances or barriers are besieging spaza shop owners.

Tracing the history of spaza shops reveals this informal sector of the retail economy’s entrenchment in discrimination and a history of struggle. Some see the spaza shop as a by-product of racial segregation policies, which once pursued and pushed forward a strategy of separate development, seeking to suppress the spirit of black African business, commerce and trading opportunities, only to ignite entrepreneurship from home or a garage.

In recent years and following the dawn of South Africa’s democratisation, the spaza shop became a battlefield for xenophobia, which unfortunately revealed the currents of hate and prejudice against foreign culture. This is a growing issue not only in South Africa but also in many parts of the world partly due to the espousing neoliberal economic globalisation policies two years after and in part due to institutional failure.

We often view the spaza shop as something very South African – part of a cultural heritage. A study by Unisa’s Bureau of Market Research (BMR) estimated 300,000 jobs are created by the spaza economy and it further contributed R9 billion to the economy per annum.

However, it is not a truly South African enterprise as the majority of shops are owned and operated by immigrant traders and foreign nationals. To a degree, it is perhaps the largest form of foreign direct investment in the country. There is also nothing strange or nefarious about spaza shop foreign national ownership. In fact, we can argue it is the hallmark showing how the country liberalised the economy and eroded the trade barriers and African border – a standard feature of all liberal economies, which by definition welcomes a free flow of people, goods, services and investment. We can also name many other foreign national companies operating in South Africa in the formal sector of the economy.

It is therefore important to take stock of the performance of South African small business owners operating in the shadow of the formal economy in retail. If there is a genuine commitment by the private and public sector to improve growth in the South African economy, a focus must fall on working to remove the barriers that prohibit growth, sustainability for South African spaza shop owners.

A recent study, The Informal Economy of Township Spaza Shops, found that South African-owned spaza shops are less competitive than foreign-run spazas.

Foreign business owners of spaza shops are outlaying more capital in informal retail startup ventures than their South African counterparts do. The study showed that the average value of the startup investment in a spaza shop for foreign shop-owners is R45,000 compared to R1,500 to R5,000 invested by South African small-business entrepreneurs.

A recent FinMark Trust study showed there is inadequate knowledge among small business owners of the benefit of credit as a financial tool. Participants in the survey indicated that they do not borrow money because they do not need it or do not believe in borrowing money. A smaller percentage of candidates do not borrow funds because they are scared or feel they do not qualify for a loan.

Having access to formal credit that will ensure enterprise growth will improve the growth of spaza shops. Programmes like this should target the poorer provinces in our country where smaller businesses rely on finance that is more informal. Improved access is necessary for large firms.

According to Small Business Connect, an online publication, in May 2015, the Minister of Small Business Development Lindiwe Zulu said the department would also look to reduce by-laws and red tape and plans to review policy to enable market access and proper registration of businesses.

Credit provision should be supported by extensive skills development programmes, because, spaza shop owners suffer from a combination of inadequate retail and merchandising knowledge and insufficient bargaining power to effectively negotiate discounts which have been discussed extensively, as pointed out in a study ‘Exploring the barriers to the sustainability of spaza shops in Atteridgeville, Tshwane’.

Crime is another problem the spaza shop owners face. Interestingly, there is a relationship between crime and pricing as discussed in a research article on competition and violence in the spaza sector in South Africa.

I recommend that government continue to find better ways to help grow this industry and equip shop owners with necessary business skills to run and manage their stores. More business skills training must be provided by the DTI, the Department of Small Business Development, local business chambers, the Wholesale and Retail Sector Education and Authority (W&RSETA).

We have also not really seen spaza business incubators – I think this type of initiative can really stimulate growth and sustainability.

South Africa needs to help these spaza shop owners grow this informal economic industry. I would recommend that government partner with NGOs or even training institutions to provide business skills courses to equip these spaza shop owners with the necessary skills and training needed to successfully run a business.

With this limited space to stock products in bulk, shop owners are forced to purchase their goods in smaller quantities, which results in the limitations of growing the businesses into a more successful and larger business.

Spaza shops in general feed off wholesalers and distribution centres mainly for commodity items, as quantity purchased can never match that of a wholesaler nor warrant an account direct with a manufacturing supplier further hindering growth. Due to smaller quantities purchased over a basket of limited items stocked, negotiating power with a supplier is limited.

All these challenges raise questions regarding the sustainability of small retailers and confirms that there is a need for local traders to be empowered with skills to manage their businesses better for their own survival.